The Godly Algorithm (75: Prehistory to civilization)

Sometime around 11,000 years ago humans living in the area directly north of modern Lebanon, Jordan and Palestine, now known as southeastern Turkey, erected megaliths—large rocks used by humans to build monumental structures. Maybe this age and location are coincidental—let us just remember that maybe always means maybe not. The place is called Göbekli Tepe. Twice as old as Stonehenge, it may be the world’s oldest “temple.” Arrayed on a hillside are five 65-foot-wide rings of standing stone pillars, up to sixteen feet tall and weighing seven to ten tons, all built by people who had not yet developed metal tools or pottery. Two large T-shaped pillars stand at the center of each ring of stones, some decorated with elaborate carvings of foxes, scorpions, lions and vultures. As the stone rings were completed their builders covered them over with dirt and built new rings atop. Centuries of successive layerings resulted in a central rounded “hill” over fifty feet high. At least sixteen more rings across the 22-acre site remain unexcavated.

Göbekli Tepe was necessarily a hunter-gatherer site, because agriculture had not yet (we’re pretty sure) been invented. Why would a wandering people construct this place? Had the religious conglomeration already begun? If so, who or what were they worshipping or celebrating? What did it mean to their minds—minds that were as equally modern as our own except that they had not yet accumulated as much culture as we have?

About half a century ago I began to notice that the phrase “11,000 years ago” seemed to be turning up with some frequency in my various readings. With this casual observance now raised to conscious level, I began noticing every time I encountered it again. And again, and again. Over the years, I have observed, “11,000 years ago” shows up in all kinds of books and articles—about earth geology, weather and climate, soils, cultural prehistory, mythology—you name it. I never quite developed the common sense to write these things down as they were being noticed, so they could be analyzed later, I just grew fascinated that they kept (and still keep) turning up in so many seemingly unrelated contexts—perhaps not unlike the way some people are “fascinated” by NDEs, and dig no deeper. I don’t know why, but pattern and meaning are implied, perhaps even strongly suggested, by “11,000 years ago.” Perhaps, I speculate, some core truth interrelates them all? Watch for “11,000 years ago” in your own readings—let me know what you find.

Developments in late human pre-history (11,000 to 5,000 years ago)

As early as 11,000 years ago agriculture had begun to be adopted. By 9,000 years ago it was fairly well developed everywhere H. sapiens had settled. For reasons unknown, peoples in many places around the world independently chose—all about the same time—to phase out of hunting-gathering and phase into living at settled locations where they could plant and harvest food in concert with the seasons. And so it came to pass that with the passing of a mere couple of thousand years a majority of people, wherever they had spread around the wide world, were farming rather than hunting and gathering.

Why did they do that? There is much speculation as to why they all started farming “so quickly” after nearly three hundred thousand years of not farming, but nobody really knows why. No doubt those old ancestors with their big modern brains could easily see that farming was a more dependable way to obtain food than going out hunting every time you got hungry—but then why hadn’t they smartly come to that realization a hundred thousand years earlier? Why did it start between 11,000 and 10,000 years ago?

They certainly didn’t fly in to an international conference to swap farming methods, so why did farming independently begin in so many places around the world, all roughly about the same time? Had a big flood or something reduced the numbers of edible wildlife(?), wiped out most edible plants(?), rearranged the depth and tilth of the world’s soils(?) by perhaps scouring away hillside dirt rich with minerals and moving it downslope to the flat, loamy stream bottoms still favored by farmers today? That verily is the situation on our farm, where the level bottoms beside the creek have topsoil ten feet deep and if the hilltops will grow grass and trees it’s sheer good luck. So why did farming began everywhere all at once? What do you think? On what evidence do you think it?

The invention of farming was one of the most significant evolutionary changes in the history of life on earth. Farming causes a qualitatively different kind of change—not only of the people who do it and fields it’s done in, but in the very way evolution itself acts upon the farmers and the fields. Farmers necessarily must live near the fields, to sow the seed, control weeds and harvest the bounty, therefore clusters of dwellings inevitably grow up near the farming fields. We call them villages.

And there they stay, accumulating garbage and artifacts in one place. If they have any success at all, the village grows until in time it is called a town, then a city, then a city-state that controls a large surrounding hinterland. The farmers soon learn to have more children than they did as hunter-gatherers, so there will be more hands for sowing seed, controlling weeds and hauling in harvests. Thus begins a trend of population increase—birthing more babies than old people are dying. Such trend continues to the present day. Yes, adoption of farming caused our contemporary overpopulation of 7.8 billion people.

At some point the town leaders always build a large granary because it’s more practical to store everyone’s grain in one defensible place than everyone building his own rodent-infested grain crib. Several consequences attend this development. Somebody begins keeping records on who put how much grain into the granary and who took how much out. The records are imprinted onto flat mud bricks using some kind of stylus. These necessary records usually initiate a path that leads to written language. Local society nearly always stratifies, so that by various means a few people are designated chiefs and sub-chiefs who exercise power of decision over all others and pilfer from the granary with impunity. Similarly, self-designated spiritual experts called priests soon emerge from the society’s spiritual overlay, ally themselves with the chief(s) and tell all the others what to believe. They too soon assert granary privileges. With high and low now established, they all domesticate small felines to constrain the rodent horde now living in the municipal granary and brave dogs to keep large carnivores away from the children.

I should mention that astronomy obviously had become remarkably sophisticated during this period. Pacific travelers had used celestial navigation around 50,000 years ago, and megaliths such as Newgrange and Stonehenge were already aligned with the solstices by 5000 years ago. Priests—the scientists of those days—were familiar not only with the movements of sun, moon and planets, they had grown adept at predicting eclipses and calculating the length of the year to within a half hour of its modern accepted value. Most interestingly, they based these accomplishments on the same principles used by science today, such as the one we call inductive reasoning—generalizing to probability from experience and observation, an obvious comparability of ancient and modern minds.

That’s about it for most prehistoric matters worth mentioning. I could add that a few inventive individuals had by this time figured out how to extract ores such as copper and tin, with the result that bronze tools and weapons quickly replaced stone tools and weapons—but that trend will be better covered later.

From pre-history…to writing…to history

Human history began when writing was invented and people started using it to record “what happened.” There are two basic approaches to these recordings we call history:

- one is to record some peoples’ biased remembrances of what happened, and

- the other is to try to record factual information about what really happened.

As one would expect, our history books include a great deal more of the former than the latter—different motivations always drive which version gets selected and printed. The “remembered” version is always easier and more satisfying to the writer—U.S. history would sound quite different from the one you know if Hitler had won the war. The factual option is by far the more difficult for, even with best intentions to be accurate, two people can look straight at the same scene and see substantially different things. I mention these obvious things only because they confront us in this section. Since I am about to presume to summarize all human history into a few paragraphs, I really should briefly expound on the human invention of writing, because the very concept of history depends on the writing down of it. If it isn’t written, it isn’t history—it’s legend. Even if it is written, it’s often still legend. As you may have noticed, truth can be hard to get at.

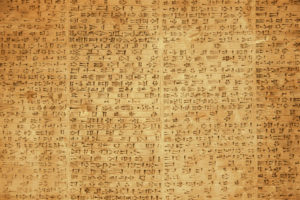

Some humans have had written history for around 5,400 years—more or less—less than two percent (1.8% actually) of the 300,000 years our species has walked the earth. We had to work our way up to it, one might say. Coherent systems for writing have been independently developed at least four times around the globe. The first is said to have been “cuneiform” script—wedge-shaped marks called pictographs, pressed into wet clay tablets using a blunt reed as stylus. Cuneiform was invented by the Sumerians in Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) around 3400 BCE. Soon afterwards (around 3200 BCE) hieroglyphs showed up in Egypt—probably influenced by, and possibly derived from, the geographically “nearby” Sumerian cuneiform.

Both forms of writing emerged out of existing pre-literate methods for hand-marked symbolic communication (these were fully modern brains, remember), and both would eventually evolve into easier-to-use alphabetic and syllabic “real writing.” As cause and effect, writing—the effect—was probably caused by practical need to keep accurate records as trading networks were developing in the region. However by as early as 2700 BCE writing had emerged upward by being used to record old tribal memories that did not survive well in the unwritten oral tradition. Use of writing to invent imaginative stories soon followed, with appearance of textual literature such as the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh and, about a century later, the Argonautica by Apollonius of Rhodes, chronicling the mythic voyage of Jason and the Argonauts in quest of the Golden Fleece.

In old China, the earliest known writing was invented and used under the late Shang dynasty around 1300 BCE. Known as “oracle bone script,” marks were etched onto animal bones and turtle shells which were then used for divination at the royal Shang court. On the American continents, the only true pre-Columbian writing (so far as we know) was developed sometime between 900 and 600 BCE in the cultures of Mesoamerica (Central America and the southern half of Mexico). An identifiably Mayan script believed to have originated around 300 BCE was discovered in recent years at a Guatemalan site known as San Bartolo.

Building atop these rudimentary understandings of “history” and “writing,” we now can more knowledgably turn to…

…Significant choices in human history

Remember that we’re now well into the cultural (third) phase of evolution, hence the rate of evolutionary change continues speeding up. And so shall we. Human history is readily available in most libraries, so we don’t need to spend much time remembering things you learned in school and can re-learn any time you wish. Accordingly, the following nuggets will briefly fill the span from the invention of writing to the present day.