ON RECONSTRUCTION…400 Years of MISSING HISTORY

A TIMELINE FOR ADVANCING EDUCATION ON SYSTEMIC RACISM:

- 1863-1877 THE FAILED PROMISE: 14 years of Reconstruction

- 1619-1865 BEFORE THE PROMISE: 246 years of Slavery

- 1877-present SINCE THE PROMISE: 144 years of Inequality & Injustice

* * *

Part One: THE FAILED PROMISE, 14 years of Reconstruction—1863-1877

(in three phases: WARTIME, PRESIDENTIAL, and CONGRESSIONAL)

1ST Phase: WARTIME reconstruction

The Emancipation Proclamation was issued in two increments:

September 22, 1862: President Lincoln issued the admonitory Emancipation Proclamation (an Executive Order known as Proclamation 95) stipulating that if the southern states did not cease rebellion by January 1, 1863, “all persons held as slaves” in the rebellious states “shall be then, thenceforward and forever free.” January 1, 1863: Lincoln issued the final proclamation. It had three limitations: 1) the freedom it promised was contingent on Union military victory, 2) it exempted southern areas that were under Union control, and 3) it was silent on slavery in all states outside the Confederacy.

Juneteenth. News of emancipation “somehow” did not get passed on to slaves in Texas for two more years. Thus it came to pass that Union General Gordon Granger, immediately upon taking command of the District of Texas at war’s end, bypassed former slave owners by issuing his newsworthy General Order Number 3: “The people of Texas are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection therefore existing between them becomes that between employer and free laborer.” In 1980—115 years after the fact—Texas became the first state to celebrate this event by declaring “Juneteenth” a holiday. Other states are following suit.

The Ten-Percent Plan. On Dec 8, 1863, President Lincoln announced the “Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction” under which 1) the process of readmission to the Union could begin if at least 10% of a Confederate state’s voters vote to pledge allegiance to the Union, and 2) it pardoned southerners who had fought against the Union and restored their property except for former slaves. Many in Congress indignantly disagreed. Seven months later Congress 3) upped the 10% to “a majority” of white males, 4) required that they also must swear a loyalty oath to the U.S. Constitution, 5) demanded that blacks receive “equality before the law,” and 6) blocked many southerners from participating in state legislative reconstruction. Lincoln exercised a pocket veto by declining to sign the bill, saying he wasn’t ready to be “inflexibly committed to any single plan of restoration.”

2ND Phase: PRESIDENTIAL reconstruction

Lincoln, reelected to a second term on November 8, 1864, was assassinated April 15, 1865—six days after Lee’s April 9 surrender at Appomattox.

Forty Acres and a Mule. On January 16, 1865, Union General William Tecumseh Sherman issued Field Order 15, directing redistribution of 400,000 acres of confiscated land in coastal Georgia, South Carolina and Florida to newly freed black families. The Freedmen’s Bureau created two months later was to give legal title for the 40-acre plots to the blacks as well as white southerners who had remained loyal to the union. It soon became evident that the mule was not guaranteed, nor—as things developed—was the land. The plan gained only limited reality—mainly in New Orleans and South Carolina’s sea islands—and by fall of 1865 the new President Andrew Johnson had enabled most former southern slaveowners to begin reclaiming their confiscated lands.

Andrew Johnson’s Reconstruction Plan, announced May 29, 1865, offered a general amnesty to southern whites who pledged future loyalty to the U.S. government; Confederate leaders were excluded from the amnesty, but they later received individual pardons. While Johnson’s plan gave southern whites power to reclaim their former property, it did nothing to deter white landowners from resuming exploitation of their former slaves, and moreover gave southern states the right to start new governments with provisional governors.

Andrew Johnson’s legacy. Across the former Confederacy there soon arose a psychological perspective which rationalized that the southern “cause” had been just; they had not actually “lost” the war, rather Lee’s surrender was but a temporary setback; and with determination they could restore the southern way of life that the war had so grievously disrupted. By the turn of the century hundreds of women’s groups were busy erecting thousands of statues memorializing Confederate generals, their troops and their cause. This perspective persists in much of the old south to the present day, though it is now widely recognized as one of the many forms of institutionalized racism in the United States.

3RD Phase: CONGRESSIONAL (aka Radical) reconstruction

The Thirteenth Amendment. Passed December 6, 1865, the 13th Amendment abolished slavery throughout the United States—with one glaring exception. It states: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction. Legislation to eliminate the slavery-by-exception clause introduced by Congressional Democrats in 2020 faces an uphill struggle to pass both houses of Congress and three-quarters of the states.

Resistance and Vigilante Terrorism. December 24, 1865: Eighteen days after the 13th Amendment was adopted, The Ku Klux Klan was founded in Pulaski, Tennessee, as a vehicle for white southern resistance to Reconstruction policies aimed at political and economic equality for black Americans. Virtually from the moment the Civil War ended, a determined quest was conducted by southern white landowners, lawyers and politicians to decisively subvert every device set up for the purpose of extending economic and political equality to African Americans and raise the Bill of Rights to reality for all citizens in the southern states. Nor were these reactionaries lacking substantial sympathy from many white citizens in the northern and western states. Anonymously-hooded KKK gangs waged incessant violence, lynchings and intimidation against both black and white reconstruction leaders, with a goal of restoring white supremacy in state legislatures and social status throughout the south. KKK members remain active today.

Black codes, incarceration and convict labor. Many people have noted the high correlation between the 13th Amendment’s Exception clause and the evolution of a modern prison system that disproportionately incarcerates black and LatinX citizens at more than five times the rate of whites, and generates significant revenue from prisoners’ slave-like unpaid or drastically underpaid labor. “Black codes” enacted across the south exploited this exception by defining as “crimes” such trivial matters as spitting on the sidewalk, ill-defined “vagrancy” and petty theft. Tens of thousands of prisoners, mainly black, have historically been leased out to plantations, coal mines and road-building chain gangs. Many states still today lease prisoners out to work free for private employers. In their more fully developed form, the black codes evolved into Jim Crow laws that imposed racial segregation, denial of voting and political rights, economic inequality and social injustice for most of another century from 1877 through the civil rights reform movement that began in the 1950s.

The Compromise of 1877. The intensely disputed presidential election of 1876 pitted New York Governor Samuel B. Tilden, Democrat, against Ohio Governor Rutherford B. Hayes, Republican. Hayes had sworn that if elected he would bring “the blessings of honest and capable self government” to the south—meaning he would restrict enforcement of the federal Reconstruction policies so widely hated throughout the south. With something to lose and much to gain, both sides tacitly agreed to an unwritten deal: If the Democrats would agree to not block Hayes ascendance to the presidency, Republicans would withdraw all federal troops from the South—thus effectively consolidating Democratic (i.e. segregationist) control over the entire region—and Hayes would even appoint one southern Democrat to his cabinet. These promises were duly kept, effectively bringing to an end the era of so-called Reconstruction and the promise it had represented for black Americans.

* * *

Part Two: BEFORE THE PROMISE, 246 years of Slavery—1619-1865

In the Year of Our Lord 1502 one Juan de Córdoba of Seville became the first known merchant to ship an African slave to the New World to work for nothing. No one remembers the slave’s name, only Córdoba’s.

Slaves in colonial America. It was “about the end of August,” wrote Virginia Governor George Yeardley to Virginia Company owners in London in the year 1619, that an English privateer ship, anchored at Point Comfort on the Virginia peninsula, unloaded “20 and odd negroes” in exchange for “victuals”—i.e., they traded slaves for food. Such a thing had never before occurred since the 104 English men and boys had arrived twelve years earlier to start a settlement near the Virginia coast, which they named Jamestowne after their King James I. And thus did the first English presence in North America mark, in the year 1619, an infamous milestone of what would grow into the institution of slavery in America. But of course that English date ignores (as is customary) the achievements of the Spanish entrepreneur Juan de Córdoba a full 117 years earlier….

A few statistics. By 1790 about 682,000 persons were enslaved in the newly-formed United States. On the eve of the Civil War enslaved U.S. residents numbered about four million. After the South’s defeat, slavery as an economic system was largely replaced by sharecropping and convict leasing.

The Three-Fifths Rule: Haggling Out a U.S. Constitution (May-September 1787). Southern delegates to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia were persuaded to discard the Articles of Confederation only after northern delegates conceded to counting each slave as “three-fifths” of a person for purposes of apportioning representatives among the thirteen states—thereby assuring slaveholding states controlling veto power over acts of the new Congress.

Insisting on a Right to Deny the Rights of Others thus persisted as the basis of the economy throughout the southern states, and as a foundation of the genteel southern lifestyle which sought to mimic that of English aristocrats. Southern white landowners’ gross wealth was made possible only by exploiting the unpaid labor of slaves whose lives were a contrast in injustice and humiliation, and plantation aristocrats knew full well that their way of life could not survive without slavery.

DECISION: Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857). In this landmark ruling the Supreme Court ruled that living or having lived in a free state did not entitle an enslaved person to freedom. The majority opinion, written by Chief Justice Roger Taney, went substantially further than the case might have merited prima facie. The decision argued that Dred Scott, as a slave owner’s property, was not a citizen, therefore he could not sue in federal court—and, moreover, that the Constitution was not meant to include U.S. citizenship for black people. Taney’s decision further declared that African Americans could never become U.S. citizens, and that Congress lacked authority to exclude slavery from U.S. territories—thereby invalidating the important Missouri Compromise of 1820. Many northerners were incensed by the decision, a fact believed to have contributed to Lincoln’s victory in the next presidential election. (Note: After this decision, the sons of Scott’s former owner purchased Dred and Harriet Scott and officially set them free. Scott died nine months later.)

* * *

Part Three: SINCE THE PROMISE:, 144 years of inequality, injustice and institutionalized racism—1877-present

Jim Crow Laws (1870s-1960s). Collectively named after a black minstrel show character, hundreds of state and local statutes legalized racial segregation—primarily, but not exclusively, in the southern states. They sought to marginalize black citizens by denying their right to vote, and by blocking them from good jobs, a decent education and many other opportunities. Such laws remained on the books, and were highly effective in achieving their intended purpose, during the century between the early days of Reconstruction and the civil rights reforms of the 1960s and 70s. Blacks who resisted compliance with these unjust laws often faced arrest, fines and jail sentences, and—not infrequently—violence and death.

DECISION: Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). In this decision—like Dred Scott, another tectonic disturbance in the ongoing evolution of U.S. civil law—the Supreme Court codified a constitutional basis for justifying racial segregation statutes. In brief, it ruled that black Americans could be required to use separate blacks-only facilities provided those facilities were equal in quality to equivalent white facilities. Plessy would stand as the law of the land for fifty-eight years, during which virtually all segregated black facilities were decidedly not equal.

Modern Legacy of Hate-Motivated Violence against black citizens. A concentration of violence against black Americans occurred in a dozen cities from 1919 to 1923. During the “Red Summer” of 1919 alone, white mobs rampaged against black neighborhoods in more than three dozen cities nationwide. The worst took place in Elaine, Arkansas, where an all-out massacre that went on for five days left 856 blacks dead—the deadliest racial incident in U.S. history. Dozens more riotous attacks on blacks and their property occurred between the world wars—black soldiers served with distinction in both wars—and again during the 1950s-1960s Civil Rights era. Numerous incidents of mob violence against African-Americans are recorded in every decade between the Civil War and the present day. These historically documented incidents of mass social violence do not include unpublicized racist-motivated violence against individual black citizens in all years.

Tulsa Race Massacre. On May 31 and June 1, 1921, white mobs—many deputized and given weapons by city officials—attacked black residents of Tulsa’s Greenwood district, at that time the most prosperous black neighborhood in the nation. Attackers looted and burned homes and businesses throughout 35 square blocks, leaving up to 300 persons murdered (official estimate), hundreds more injured, and permanently displacing thousands who fled the area,

DECISION: Brown v. Board of Education (1954). In this landmark decision the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools—even if the separate black and white schools were equal—inherently violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The decision reversed lower court rulings that segregated public facilities were legal so long as the facilities for blacks and whites were equal—i.e., the “separate but equal” doctrine established in 1896 by Plessy v. Ferguson. Though focused on the board of education in Topeka, Kansas, Brown consolidated several cases arising in Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, Delaware and Washington, D.C. where, in each case, African American students had been denied admittance to certain public schools under laws that allowed segregation based on race. Brown v. Board of Education signaled the end of racial segregation in United States schools.

1980-present: Reaction against 1950s-60s civil rights gains. Americans born before 1950 remember the irrational hate-filled prejudice of many white Americans following the Supreme Court’s rulings against school segregation, and during the integrative busing orders that followed. Racist reaction against civil rights measures implemented in the quarter century after 1954 intensified after 1980; efforts to un-do those rights persist to the present day. The extreme violence perpetrated against unarmed citizens peacefully exercising their Constitutional right of assembly on the Edmund Pettus bridge in Selma, Alabama—and against black teenagers requesting service at a soda fountain—and against would-be black voters dispersed by water cannons, police dogs and bone-crushing night sticks—these scenes do not fade from memory. More contemporary hate-motivated crimes—mass shooting of black worshippers in prayer meeting at church, violence against peaceful marchers in Charlottesville—these seem but a re-living of those bad old days to those who remember, and wonder what gains have been made.

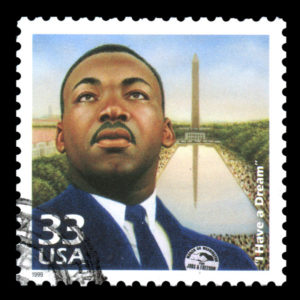

Systemic Racism is evidenced when white citizens unknowingly perceive and condemn as “rioting” the justified anger of African Americans against seemingly endless, repeating provocations. Prominent examples are the fires set in cities nationwide in reaction to the murder of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., on April 4, 1968, and—over a half century later—the globally witnessed murder of George Floyd on May 25, 2020. Unlike hooligan riots, the mayhem triggered by these and comparable atrocities in fact represents a boiling over of pent-up frustration, anger and resentment over long decades of experienced discrimination, ill treatment and racist violence by whites against blacks. Violent outbursts after Floyd’s murder responded especially to continuing police killings—over, and over, and over again—of blacks detained for trivial or contrived offenses. White failure to distinguish between common rioting and frustrated black violence after centuries of powerlessness against extreme unjust treatment is, by definition, institutionalized systemic racism.

Police brutality and de facto bias against black Americans. Slowly but steadily, America’s local police have been so militarized over recent decades that they now look, are trained, and behave more like soldiers on deployment than cops on the beat. We should all regret this fundamental change from the traditional fair-minded cop walking the neighborhood beat in friendly relationship with community members, intent on ensuring a safe neighborhood for all. Civic-minded citizens must also regret how easy it is to lose count of the black Americans wrongfully killed after traffic stops and other situations that were trivial, contrived or evidenced sheer bad judgment by anonymous, depersonalized police. Such incidents continue without apparent sign of letting up or evidence of justice replacing injustice. The victims’ very names have become emotional triggers: Daunte Wright, 20; Rayshard Brooks, 27; Daniel Prude, 41; George Floyd, 46; Breonna Taylor, 26; Atatiana Jefferson, 28; Aura Rosser, 40; Stephon Clark, 22; Botham Jean, 26; Philando Castile, 32; Alton Sterling, 37; Freddie Gray, 25; Janisha Fonville, 25; Eric Garner, 43; Michelle Cusseaux, 50; Akai Garley, 28; Gabriella Nevarez, 28; Tamir Rice, 12; Michael Brown, 18; Tanisha Anderson, 37…. These are but the most notorious cases of the past six years, 2014 through 2020, during which police in the United States killed 7,680 people “in the line of duty.” One-fourth of those killed were black. Black citizens are 13% of the U.S. population.

The slaveowner mindset is alive and well among us today. The modern equivalent of the slaveholder South exists in the extreme inequality between fabulously wealthy owners of mega-corporations, controlling more wealth than many whole nations, and their poor employees black and white—paid minimum wage, advised to get on welfare, subject at all times to discrimination and unemployment when their corporate employers cut costs by sending jobs abroad to low-wage nations. In every historical period including the present, institutional racism and the predisposition to tolerate slavery is only a matter of degree.